5 Results Of The Spanish American War

- The Spanish American War History

- 5 Results Of The Spanish American War Summary

- Spanish American War In The Philippines

- Effects Of The Spanish American War

Spanish-American War: Results. Peace was arranged by the Treaty of Paris signed Dec. 10, 1898 (ratified by the U.S. The Spanish Empire was. Results of the war-Cuba-Philippines-Guam-Puerto Rico-Cuban Protectorate. A large island nation about 90 miles off the coast of Florida that was a colony of Spain until freed in the Spanish-American War. Guam-The largest and southernmost island in the Marianas-was. Of State John Hay say about the war in Cuba? At the end of the Spanish American War with the signing of the Treaty of Paris what did the U.S. Gain as a result? Results of the Spanish-American War. The Spanish American War lasted only about were the U.S. Won almost every major battle. But the first battle of the war took place in a Spanish colony on the other side of the world—the Philippine Islands. On April 30, the American fleet in the Pacific steamed to the Philippines. The next morning, Commodore George Deweygave the command to open fire on the Spanish fleet at Manila, the Philippine capital.

The United States started as a string of British colonies, and the oppression of the colonies eventually led to an intense resentment towards the system of mercantilism. However, centuries of time, the end of the frontier, and a slew of new books promoting an expanded manifest destiny led to changes in the American ethos. Industry required new sources of raw materials and new markets to sell in, and so as the nation moved closer to the 20th century, the demand for America to acquire her own colonies grew.

A central feature of imperialism is ethnocentrism, the belief that one’s culture is inherently superior to others. Working from this assumption, various intellectuals created diverse moral justifications for the oppression and subjugation of foreign peoples. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power upon History insisted that powerful navies had decided the European power struggles for the previous two centuries. His well-read book advocated a modern navy with battleships at its core to protect a strong merchant marine that would trade with colonies. Josiah Strong, in Our Country, argued that it was America’s Christian duty to expand our American Protestant ideals to the rest of the world. Lewis Henry Morgan described in Ancient Society a social ladder consisting of savagery, barbarism, and civilization. Western Europe and US reigned supreme at the highest level, and Morgan posited that members of the lower rungs could be ethically subjugated and their moral precepts replaced with ours.

While America now yearned for colonies of her own, an inconvenient situation presented itself in that all of the islands worth claiming had already been taken by European powers. America needed to wrestle an existing colony from an empire but it could not, as a free nation, initiate a war for such purposes. The solution was to simply hijack another war. Cuban insurgents had been fighting for independence from Spain for years. America could easily “liberate” Cuba and claim new territories.

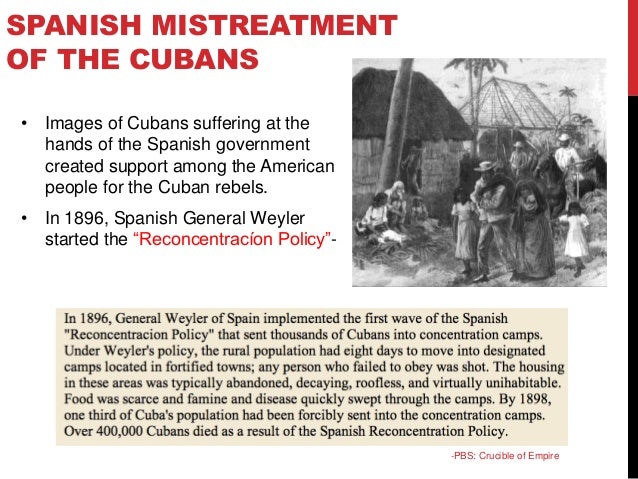

Cuban rebels blended in with the civilian populace and fought the stronger Spanish forces using guerrilla tactics. The Spaniards could not possibly kill everyone while maintaining respectability and so, to separate the rebels from the people, Spanish General Weyler established reconcentration camps in Cuba for all civilians. Anyone outside would be considered a rebel and would be killed. The conditions inside the camps were crowded, unsanitary, rife with contagious diseases. Innocent civilians who, for various reasons remained outside, were murdered along with the rebels. American yellow journalists William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer competed with each other to find—or create—the worst reports of Spanish atrocities. These stories inflamed the public who saw Weyler as a “butcher.”

Furious at the Spanish Empire, Americans eagerly awaited further news. In a letter intercepted by the Cuban rebels and published by the American press, Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, Spanish ambassador to the US, wrote that President McKinley was “weak and a bidder for the admiration of the crowd.” Then, on February 15, 1898, the USS Maine, anchored in Havana harbor, exploded. Fueled by a steady stream of ill-informed reports from yellow journalists, the bloodthirsty public immediately blamed Spain as saboteur. McKinley demanded, among other things, that Spain immediately end the fighting and reconcentration camps. Spain promised reforms but ignored his other two demands: mediation by McKinley and Cuban independence. McKinley told Congress “the war in Cuba must stop” Congress responded by declaring a de facto war on Spain. To appease rightfully-held fears of imperialism, Congress included the Teller Amendment stating that the US did not intend to annex Cuba. Spain had no choice but to declare war on America and thus the Spanish–American War officially began.

Before the drama in Congress, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt cabled George Dewey, commander of the Pacific Fleet, to destroy the Spanish fleet at Manila, if we went to war with them. Following the declarations of war, Dewey easily defeated the much smaller Spanish fleet, becoming a war hero in the process. Abetted by Dewey’s quick victory in the Philippines, McKinley pushed a joint resolution through both houses of Congress that annexed Hawaii. American sugar planters had deposed the Hawaiian queen, Lili’Uokalani five years earlier and sought annexation but anti-imperialist senators had blocked it.

Americans finally landed on the shores of Cuba, though haphazardly. It took many hours to unload the men and supplies, including the horse of Theodore Roosevelt, who with his Rough Riders took Kettle Hill. Though won at great cost, the attack cleared the way for the successful assaults on San Juan Hill and San Juan Heights, two hills overlooking Santiago harbor. The Spanish fleet in the harbor tried to flee but the American fleet sunk or ran aground all of the Spanish ships killing 323 but losing only one American. Perched atop Santiago, Americans forced the Spanish surrender after only two weeks. Another week later, America took Puerto Rico and quickly followed with an uncontested seizure of Guam. When American troops arrived in the Philippines, the Spanish surrendered immediately. Our “splendid little war” concluded in less than four months.

In December of 1898, after months of negotiations that failed to include the Cubans or Filipinos, Spain and the US signed the Treaty of Paris. The treaty freed Cuba, gave Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States and sold the Philippines for $20 million. Unlike previous treaties, the newly acquired territories were given no promise of future statehood or the rights of citizens. The inhabitants were considered inferior people incapable of self-governance. America became a colonial empire, the exact thing it had once despised and fought against.

The Spanish American War History

Summary

Puerto Rico, which became an American protectorate under the Treaty of Paris, was very poor. US troops were welcomed in 1898, and the Puerto Ricans greatest hopes were for increased rights and a better economy. Puerto Rico's experience under US rule was more positive than that of the Philippines. In 1900, Congress passed the Foraker Act, which set up a civil government for the Puerto Ricans, and gave the Puerto Ricans some amount of self-government. However, most power still belonged to officials appointed by the US government, a fact which angered many Puerto Rican natives. The US went right on working to Americanize Puerto Rico, importing institutions, language, political systems, and the like. However, the US was always vague about Puerto Rico's eventual political future. As a result, a resistance movement sprung up, led by Luis Munoz Rivera. Gradually, the US granted more and more concessions to the Puerto Ricans, and in 1917, Puerto Ricans were made US citizens, with full citizens' rights. In addition, the Puerto Rican immigrant community in the US was largely a result of the relationship that developed between the US and Puerto Rico as a result of the Spanish-American War.

In Cuba, the US installed a temporary military government after the war. At first, General John Brooks was sent in as leader of the occupation government, but he proved too antagonistic to the Cuban population. The US soon installed a second occupation government under the direction of the former leader of the Rough Riders, the newly promoted General Leonard Wood. Wood's main goal was to improve Cuban life. He modernized education, agriculture, government, healthcare, and so forth. Wood also had Havana's harbor deepened, in preparation for a higher volume of trade with the US. At the same time, research by Dr. Walter Reed, begun during the war, located the mosquito that carried yellow fever. Wood followed Reed's advice, and destroyed many of the swamps, marshes, and pools of water where these mosquitoes bred, reducing the frequency of yellow fever cases.

But although Wood seemed to have a knack for Cuban government, and the US would probably have liked to keep the island, there still was the problem of the Teller Amendment. In 1902, the US did indeed honor its promise in the Teller Amendment, and, while it did not withdraw from the Philippines or Puerto Rico or Guam, did withdraw from Cuba. However, afraid that another great power might conquer Cuba, the US forced the Cubans to write the Platt Amendment into their new constitution, which was ratified in 1901. Among other things, the Platt Amendment gave the US a Cuban base (Guantanamo) that remains to this day. The Cubans, although they always followed the Platt Amendment, deeply resented that the US left a military base behind, which they did not feel truly lived up to the Teller Amendment's promise to withdraw entirely from Cuba after the war.

Commentary

5 Results Of The Spanish American War Summary

For Puerto Rico, life as a US protectorate had its ups and downs. On the positive side, the US improved many areas of Puerto Rican life, providing more education, improving sanitation, and building roads. On the negative side, there always were a certain number of Puerto Ricans who chafed under American rule and who desired independence from the US, such as Luis Munoz Rivera and his resistance movement. Nonetheless, Puerto-Rican American relations were far more peaceful than US-Philippine relations.

Spanish American War In The Philippines

A problematic legal issue arose over the fate of the Philippines and Puerto Rico. As protectorates, many wondered, did the US Constitution apply to the people there or not? The dispute was finally cleared up in a series of 1901 decisions known as the Insular Cases, in which the Supreme Court found that the Constitution and other US laws did not necessarily apply to colonies. Because of the decision, the task of deciding which US laws did and did not apply to the colonies fell to Congress.

Effects Of The Spanish American War

General Leonard Wood's Cuban occupation seemed fairly reasonable and willing to compromise, except for one major blemish. When Wood set up the occupation government, which granted some small amount of self-government to the Cubans, he put structures in place so that Afro-Cubans would be kept out of politics.